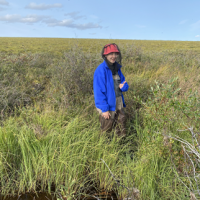

There is no doubt that UMass’ sphere of influence spreads far beyond the Pioneer Valley. Alumni, understandably, live and work all over the world. The same is true for the research interests of the current students. One may not expect that research to spread as far north as the Arctic, but indeed it does. Our highlight is on one Brady Bell. A civil and environmental engineering major currently in their junior year and on the Renewable Energy track in iCons, Brady took part in a five-year-long research project funded by the National Science Foundation, along with a helping hand from Dr. Colin Gleason (Civil and Environmental Engineer, UMass Amherst).

Their research focused on active layer depth and better understanding permafrost properties of transitional zones between alluvial and beaded streams in the Arctic. Most of their data was gathered by surveying up to 16 different streams, taking GPS data, water quality measurements, and permafrost measurements. Brady personally researched seven of those streams. “This mission could have gone one or two ways,” they told me. “We could have said ‘okay, this is our hypothesis and this is what we want to gather.’ Or, we could go out there with the idea that, while these theories had not yet been investigated, we would seek to collect a wide array of data that we could further draw conclusions from later on.”

Their team was the first to survey these tundras. To analyze those unknowns and to provide meaningful data for generations to come was theirs to pioneer.

![]() But, every great research team needs to start somewhere. Beginning with a year-long class to prepare, they started gearing up and planning out their research in the spring. One flight to Fairbanks and 10 days of quarantine later, they found themselves amidst a team of researchers from all over the world. Working out of the Toolik Field Station, they would subsequently drive anywhere between 1-2 hours to the rivers they would survey. One factor would prove to be a pesky villain in their research - the weather. Unpredictable in its nature and disruptive in their mission, certain equipment, such as water quality probes, would have to be left behind should the clouds open up with rain.

But, every great research team needs to start somewhere. Beginning with a year-long class to prepare, they started gearing up and planning out their research in the spring. One flight to Fairbanks and 10 days of quarantine later, they found themselves amidst a team of researchers from all over the world. Working out of the Toolik Field Station, they would subsequently drive anywhere between 1-2 hours to the rivers they would survey. One factor would prove to be a pesky villain in their research - the weather. Unpredictable in its nature and disruptive in their mission, certain equipment, such as water quality probes, would have to be left behind should the clouds open up with rain.

Years ago, you would find a younger Brady at perhaps a survival camp or just on a hike appreciating the wilderness and the natural world. Should you tell them that ten years later they would find themselves surveying the tundras of Alaska, they may not have believed you. But that unique mission, more importantly, Brady’s intangible impact on it, was very much real.

![]() Their impact was not always easily orchestrated. Quite frankly, their team had challenges nearly every step of the way. Brutal weather conditions, treacherous hikes, and having to make adjustments on the fly were some of their biggest obstacles. “Being in a team was vital, especially when we’re studying something that none of us knew anything about,” they recalled. How did they mend that issue? “Each of us specialized in a certain part of the project,” they revealed, “so that we would individually become, in a way, experts.” Brady’s main role was that of camp manager, safety lead, and data lead, resulting in them being in charge of nearly all quarantining protocols and even going as far as being in charge of coordinating medical evacuations via helicopter (though luckily, things never descended to that level of emergency).

Their impact was not always easily orchestrated. Quite frankly, their team had challenges nearly every step of the way. Brutal weather conditions, treacherous hikes, and having to make adjustments on the fly were some of their biggest obstacles. “Being in a team was vital, especially when we’re studying something that none of us knew anything about,” they recalled. How did they mend that issue? “Each of us specialized in a certain part of the project,” they revealed, “so that we would individually become, in a way, experts.” Brady’s main role was that of camp manager, safety lead, and data lead, resulting in them being in charge of nearly all quarantining protocols and even going as far as being in charge of coordinating medical evacuations via helicopter (though luckily, things never descended to that level of emergency).

At the end of the day, all things must come to an end. While Brady’s research mission may be concluded, their research and surveying will prove necessary for all sorts of scientists across many fields. From the tundras of North Slopes, to the peak of Mount Pollux in Amherst, to the classrooms at UMass, Brady Bell has left their mark on iCons and UMass’ history books for the foreseeable future.

Stay Connected